Long-term issues with Lyme disease and COVID-19 infections are strikingly similar, and much can be learned from a disease that stems from a tick bite, medical experts say.

This article was written by Louise Esola for Business Insurance. (Photo credit @ Business Insurance)

Symptoms of Lyme disease and COVID-19 have been described as equally debilitating and mysterious.

Long COVID is “similar to a Lyme disease type of situation, where you’re seeing not just one condition,” but possibly neurological, pulmonary and cardiac impacts, said Jennifer Laver, a partner in the Mount Laurel, New Jersey, office of comp defense firm Weber Gallagher Simpson Stapleton Fires & Newby LLP. “There are multiple layers, so it’s a lot more complicated than normal” workers comp claims, Ms. Laver said.

In March 2020 — before some 20 states passed COVID-19 presumptions — Ms. Laver began drawing comparisons between COVID-19 and Lyme disease to explain how a COVID-19 infection might be compensable in workers comp, based on occupations and likely exposure to the pathogens.

However, despite the similarities, Lyme disease in comp “is very rare and only a few states allow for it. It’s not something we see,” said Mark Walls, Chicago-based vice president of client engagement at Safety National Casualty Corp.

Lyme disease was briefly in the spotlight in workers comp in April when New York lawmakers attempted to make it a compensable illness. That bill died in committee, as was the case in other states that attempted to create a presumption over the past few decades. For example, West Virginia legislation on the subject failed to advance in 2010.

California has had a presumption in place since 2002 for certain first responders, such as those working in areas where they are exposed to ticks, and for state Conservation Corps members.

While Lyme disease is compensable in some cases if the worker can show he or she was bitten by a tick at work, data and case management experiences are hard to come by, even in a presumption state such as California, according to experts. And the workers comp industry has little to go on in comparing Lyme disease and long COVID in terms of claim management and outcomes.

“It’s the same problem for all of these long-tail diseases,” said Lorraine Johnson, Los Angeles-based CEO of the advocacy group LymeDisease.org and principal investigator for its research arm, MyLymeData.

“The medical system does a pretty good job of handling acute illness — something that’s easy to diagnose, easy to treat and then they send you on your way — but they do not do a good job with chronic diseases, or with a long-tail illness that persists after an infection. And that’s the situation here,” she said, adding that the lack of medical experience leads to a lack of understanding when it comes to insurance coverage such as workers comp and disability.

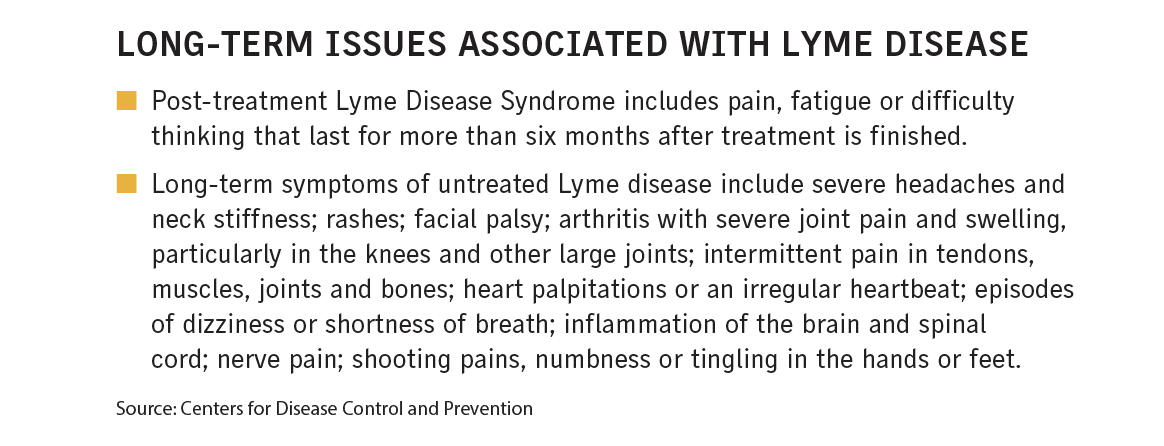

Lyme disease often goes undiagnosed, as there are no “good” medical markers for the long-term issues associated with it, and the availability of medical specialists attuned to the disease is scant, Ms. Johnson said.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates that cases go underreported by a factor of 10, and LymeDisease.org, in a study published this year, found that 86% of the reason a Lyme disease sufferer’s treatment is delayed is due to “inadequate physician education.”

Whether attention to long COVID could lead to interest in Lyme disease remains to be seen, experts say.

“COVID changed everything,” said Brian Allen, Salt Lake City-based vice president of government affairs, pharmacy solutions, for Mitchell International Inc., a subsidiary of Enlyte Group, which provides workers comp services.

Historically, it’s been common for Lyme disease claims in workers comp to be denied on the premise that a person can be bitten by a tick anywhere, experts say.

Several large workers comp insurers declined to speak on the issue, as did many third-party administrators.

State data is not readily available. Connecticut, a Lyme disease hot zone and one of the few states that tally occupational exposure, reported just 45 work-related tick bites that led to Lyme disease in 2021. The Maine Department of Labor last reported on Lyme disease in 2011, when there were 32 occupational cases; historically, the highest total reported in the state was 83 cases in 2006.

The lack of occupational illness claim activity likely stems from prepandemic reasoning, when infectious diseases were typically not covered for most workers outside of a hospital setting, experts say. That was before 2020 when a wave of states passed COVID-19 infectious disease presumptions that the industry had argued were flawed, as in many cases the virus could be contracted anywhere.

In 2016, a letter written by a Miami Beach, Florida, city manager made headlines when, referring to two denied claims for the then-common Zika virus contracted by two police officers, he called on the officers to provide proof that they contracted the virus while on duty and said they must “identify the specific infected mosquito” that caused their illness.

Referring to the relationship with Lyme disease and similar illnesses, Glenn Shor, an adviser for the National Council for Occupational Safety and Health and a lecturer and researcher with the Center for Occupational and Environmental Health at the University of California at Berkeley, said, “How do you determine whether it’s an occupational exposure that would be eligible for workers comp?

“It’s a situation that is case by case and where you’ve got to have the evidence of the exposure, the right occupation, where that exposure could have taken place. … I don’t think you’re ever going to know it’s 100% related to work, because people can be exposed, just like with COVID, in many places.”

Workers comp claims that are denied rarely wind up in the courts, often because of a lack of medical evidence, experts say. When cases are litigated, the results are mixed.

In 2021, an appeals court in New York denied compensability on “insufficient medical evidence” for a security guard who filed a claim for Lyme disease six years after being bitten by two ticks while out on patrol. Conversely, in 2013, that same appeals court ruled that a construction worker’s Lyme disease was compensable, as he had been working in a wooded area and “voluminous” medical evidence connected a 2008 tick bite to his muscle weakness and eventual total disability.

Also in 2013, an appeals court in New Jersey ruled that a park service worker’s Lyme disease was compensable as she patrolled areas where ticks were and often pulled ticks off her clothing.

“It’s always been case by case,” said Steve Wurzelbacher, Cincinnati, Ohio-based manager of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Center for Workers’ Compensation Studies at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Data on Lyme disease is “pretty rare and we haven’t had much that’s been published in the review literature,” Mr. Wurzelbacher said.

Data starts to emerge on ‘mysterious’ condition

The mystery of long COVID continues to baffle health care providers and the workers comp industry, though recent data and experience are shedding some light, according to experts.

The National Council on Compensation Insurance reported in October that 24% percent of COVID-19 workers compensation claimants have or have had long COVID. Overall, 20% of non-hospitalized and 47% of hospitalized workers with admitted COVID-19 claims developed long COVID, according to the Boca Raton, Florida-based ratings agency.

NCCI relied on claims data extending through the first quarter of this year for claims with accident dates between March 2020 and June 2021. The data “does not fully reflect the potentially longer-term impacts of long COVID,” NCCI said.

It marked the first time the ratings agency studied an infectious disease such as COVID-19, and long-term issues that extend beyond the study years will continue to be a focus, NCCI actuary Robert Moss said.

“This long COVID issue … is so mysterious, and there’s nothing to compare it to,” Mr. Moss said.

The report highlighted the number of medical specialties involved in caring for a patient with long COVID, which comprise more than 150 medical codes associated with the diagnosis and are grouped into eight symptom groups. The most common, in order, are pulmonary and cardiovascular, followed by neurological, systemic, endocrine, autoimmune, mood disorders and sleep disorders.

***DISCLAIMER: The article states that Lyme disease is rare. (It isn't). They are comparing the number of cases to those with COVID-19.

Click here to read the rest of the article from Business Insurance.

Click here to read more blogs.

The above material is provided for information purposes only. The material (a) is not nor should be considered, or used as a substitute for, medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment, nor (b) does it necessarily represent endorsement by or an official position of Global Lyme Alliance, Inc. or any of its directors, officers, advisors or volunteers. Advice on the testing, treatment or care of an individual patient should be obtained through consultation with a physician who has examined that patient or is familiar with that patient’s medical history.