The long-term form of Covid-19 has something in common with other forms of chronic illness — strange and varied symptoms, lasting debilitation, no certain treatment. But unlike other such conditions, which tend to creep up on society, long-haul Covid arrived suddenly, creating a large pool of sufferers in a short period of time and afflicting frontline medical workers and younger patients in large numbers.

This created a sense of immediacy and urgency absent from other chronic-illness debates and a constituency for research and treatment among a population — doctors, especially — that’s often skeptical of difficult patients and mystery illnesses.

But already with long Covid you can see the usual structure of chronic-illness controversies reasserting itself. Recent articles in The Atlantic and The New Yorker cover the emerging lines of debate, which pit patient advocates urgently seeking treatment against scientists following cautious research protocols.

Meanwhile, among friends naturally inclined to skepticism, I can see the initial sympathy inspired by long Covid giving way to the doubtfulness that hangs around chronic fatigue syndrome, or fibromyalgia, or the chronic form of Lyme disease. Liberals who eye-roll at the enthusiasm for, say, ivermectin may do the same for the weirder experiments in treating chronic Covid symptoms. Conservatives who are critical of liberal public-health policies increasingly regard long-term Covid as a kind of blue-state hypochondria.

I understand these ideas because for a long time, despite close relationships with people who suffered from chronic illness, I shared some of them. Most notably, I shared a common idea of what chronic illness is like — imagining a kind of Victorian fainting-couch experience, a hyperactive fixation on tingles and twinges, an exaggerated version of the fatigue that comes after you’ve stayed up with a newborn or the aches you feel after exercising for the first time in months.

Then I got sick myself.

It was the spring of 2015, and my wife and I were moving, with our two young daughters, from Washington, D.C., to Connecticut, where we had both grown up. I had always nursed a fantasy of escaping the metropolis for rural isolation, and after our Capitol Hill rowhouse sold for an absurdly appreciated figure, we plowed the money into a 1790s New England farmhouse with three acres of pastureland, a barn and an apple tree, a guest cottage and a pool.

It was expensive, a definite reach, but we were young, energetic and healthy, and a reach was what I particularly wanted — a place that would force me outside, tear me away from the internet, the sedentary pundit’s life. On the day the house inspection revealed a daunting list of issues, I walked the overgrown paths on the property, watching a family of deer dart through the meadow. Then I looked up at the main house perched above me and thought with satisfaction: Yes, this is what I want.

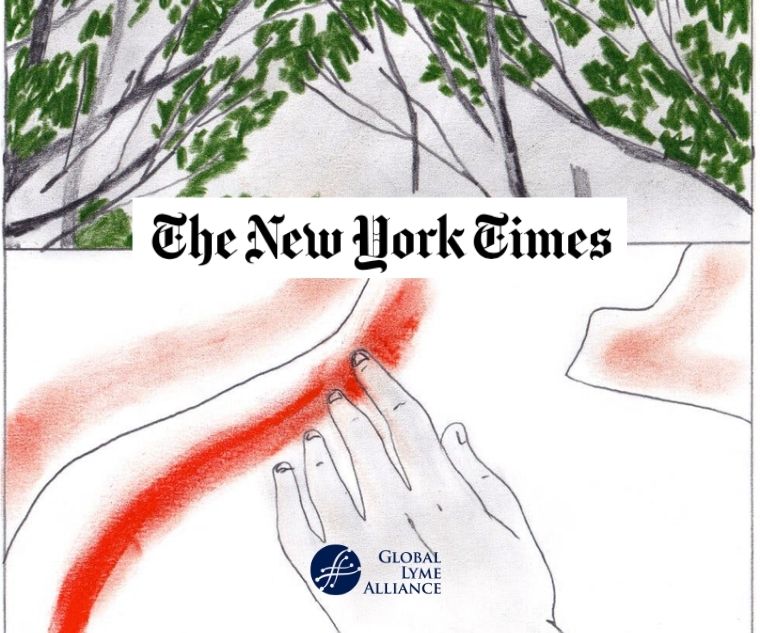

A few days later we were back in Washington, having set up the closing dates so that we could spend the summer wrapping up our old life. It was a rainy morning. I awoke with a stiff neck and went to the bathroom to find a red swelling, a painful lymph node just down from my left ear.

I came out and sat rubbing my neck, and my wife came up behind me, her voice unusual: “Ross.”

She was holding a pregnancy test, the telltale strip faint but clear. Our third child.