If you have ever found a deer tick crawling on your shirt or sock, you know how difficult they can be to spot. Adult females are about the size of a small freckle and nearly as flat (at least until they begin feeding and plumping up on your blood), and immature ticks—the nymphs—are even smaller. Now, scientists at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (CAES) have discovered an adult female deer tick that could even more easily escape notice, because it is half the normal size.

The interest in deer ticks (Ixodes scapularis) stems largely from their connection to Lyme disease. Infected ticks transmit the disease pathogen, a bacterium, after they latch onto the skin and begin engorging themselves on human blood. The finding of the dwarf female comes at a time when the proportion of infected deer ticks has skyrocketed, says study senior author Goudarz Molaei, Ph.D., associate research scientist at the Center for Vector Biology & Zoonotic Diseases at CAES and associate clinical professor at the Yale School of Public Health. Molaei is director of the CAES Tick-Testing Laboratory, which encourages residents to submit ticks that they find on their bodies so they can be tested for the Lyme bacterium, as well as other pathogens. Until recently, the tick-testing lab received fewer than two dozen ticks during March and April, he says, “but, partly because of unusually warm winters over the last two years, we now receive more than 2,000 ticks in those two months.” Similarly, he reports, people typically submit about 50 ticks for the entire winter—December, January, and February—but in the winter of 2016-17, the program received nearly 800.The miniature tick was just 1.5 millimeters long, compared to the typical 3-millimeter length of an adult female deer tick. As a nymph, it may have been tinier yet. The discovery and its importance are described in a new paper published in the Journal of Medical Entomology.

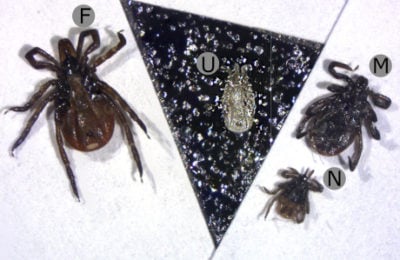

[caption id="attachment_4445" align="alignright" width="331"] The dwarf deer tick (U) identified at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station has all the same physical features of a normal adult female deer tick (F), but it is about half the size. (This image was taken after the dwarf tick specimen was affixed to carbon paper and sputter coating for scanning electron micrography; the original coloration of the specimen was similar to the female deer tick shown here.) Also pictured are an adult male deer tick (M) and a nymph (N) of the same species (Ixodes scapularis). (Photo credit: Molaei research group)[/caption] In addition to the increasing number of ticks, a greater percentage is infected with the Lyme disease pathogen. “Historically, based on our studies, the infection rate has been in the range of 27 to 32 percent, but this year so far, we have recorded up to 38 percent of ticks infected, and in some regions the infection rate reaches up to 50 percent. That is quite unusual,” Molaei says. When the testing program initially received the minuscule tick in November 2015, Molaei was stumped, as were other experts that he consulted. While it looked like an adult deer tick, it was way too small. Its identity was finally revealed after paper co-author John Soghigian, Ph.D., joined Molaei’s laboratory at the CAES as a postdoctoral research scientist last year. Soghigian used molecular methods to meticulously examine DNA obtained from the tick’s leg and followed up by obtaining an exceptionally close-up view with a scanning electron microscope. Both established that it was indeed a deer tick, which is also sometimes called a blacklegged tick. It was also the first member of that species shown to exhibit dwarfism, or nanism. Part of the significance of the finding lies in the recent detection of a few additional ticks with abnormalities, such as extra legs, in small sampling sites in Wisconsin and New York, as well as additional abnormal deer ticks found near the site of the dwarf individual. “What’s interesting is that they’re all popping up at the same approximate locations,” says Soghigian. [caption id="attachment_4446" align="alignright" width="343"]

The dwarf deer tick (U) identified at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station has all the same physical features of a normal adult female deer tick (F), but it is about half the size. (This image was taken after the dwarf tick specimen was affixed to carbon paper and sputter coating for scanning electron micrography; the original coloration of the specimen was similar to the female deer tick shown here.) Also pictured are an adult male deer tick (M) and a nymph (N) of the same species (Ixodes scapularis). (Photo credit: Molaei research group)[/caption] In addition to the increasing number of ticks, a greater percentage is infected with the Lyme disease pathogen. “Historically, based on our studies, the infection rate has been in the range of 27 to 32 percent, but this year so far, we have recorded up to 38 percent of ticks infected, and in some regions the infection rate reaches up to 50 percent. That is quite unusual,” Molaei says. When the testing program initially received the minuscule tick in November 2015, Molaei was stumped, as were other experts that he consulted. While it looked like an adult deer tick, it was way too small. Its identity was finally revealed after paper co-author John Soghigian, Ph.D., joined Molaei’s laboratory at the CAES as a postdoctoral research scientist last year. Soghigian used molecular methods to meticulously examine DNA obtained from the tick’s leg and followed up by obtaining an exceptionally close-up view with a scanning electron microscope. Both established that it was indeed a deer tick, which is also sometimes called a blacklegged tick. It was also the first member of that species shown to exhibit dwarfism, or nanism. Part of the significance of the finding lies in the recent detection of a few additional ticks with abnormalities, such as extra legs, in small sampling sites in Wisconsin and New York, as well as additional abnormal deer ticks found near the site of the dwarf individual. “What’s interesting is that they’re all popping up at the same approximate locations,” says Soghigian. [caption id="attachment_4446" align="alignright" width="343"]

Goudarz Molaei, Ph.D., director of the Tick-Testing Laboratory at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, reports that deer-tick numbers have been rising, and a higher proportion of the ticks are infected with the bacterium that causes Lyme disease in humans. Molaei is also associate research scientist at CAES and associate clinical professor at the Yale School of Public Health. (Photo credit: Molaei research group)[/caption]

Goudarz Molaei, Ph.D., director of the Tick-Testing Laboratory at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, reports that deer-tick numbers have been rising, and a higher proportion of the ticks are infected with the bacterium that causes Lyme disease in humans. Molaei is also associate research scientist at CAES and associate clinical professor at the Yale School of Public Health. (Photo credit: Molaei research group)[/caption]

The localization of the abnormalities suggests that environmental factors may be involved, he says. Such factors range from higher-than-normal temperatures and humidity levels, like those seen in Connecticut over the past couple of years, to the presence of pesticides and other chemicals in the environment. Some European research groups are beginning to link heavy metals to increased abnormalities in ticks there, but Soghigian noted that additional studies are necessary to draw conclusions about U.S. populations. “At this point, we can only speculate about what’s causing what we are seeing here in the United States,” he acknowledges.

The larger question is what dwarfism or other abnormalities may mean to disease transmission in humans. Again, the answer is unclear. Molaei explains, “There are a few reports in the literature indicating that some ticks with abnormalities may have better vector competence, meaning that they are better able to transmit disease agents, but a greater number of specimens with these types of abnormalities is required in order to properly investigate that.”

-2.jpg)