by Jennifer Crystal

At the 2019 International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society (ILADS) conference in Boston, infectious disease specialist Francine Hanberg, M.D. gave a talk about the causes and manifestations of “Lyme brain” called “Neuropathology in Patients With Late Lyme Disease and Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Symptoms: CNS Vasculitis, Hypoperfusion, Inflammation and Neuropathy.” Since I had suffered from many of the symptoms associated with Lyme brain—such as short-term memory loss, confusion, brain fog, word repetition, and word loss— her talk caught my attention.

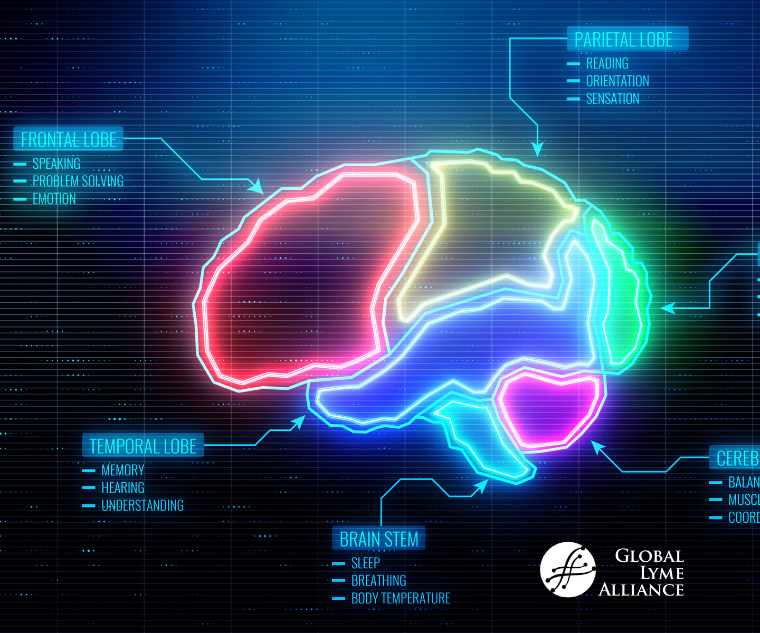

Dr. Hanberg focused on documenting the severity of tick-borne diseases through brain imaging and neurodiagnostic studies. I was struck by her study “Watershed Sign As a Marker for Late Lyme Neuroborreliosis.” “Watershed” areas of the brain, it turns out, simultaneously receive blood from different arteries, the way a creek might receive water from different outlets that eventually drain into a river.

In a previous post, I described Lyme-brain as a feeling of “molasses seeping through your brain, pouring into all the crevices until your brain feels…[as if] it will explode.” Reviewing Dr. Hanberg’s slides, I could imagine exactly where my “molasses” was pouring—or, rather, I could see where the inflammation in those areas once made my own brain feel so heavy with pressure.

Because Lyme tends to affect watershed areas, cognitive impairments from the disease are usually broad-spectrum, rather than localized as with stroke. As described in the book Lyme Brain by Nicola McFadzean Ducharme, N.D., a study done by neuropsychologist Marian Rissenberg, Ph.D. and Susan Chambers, M.D. explains the major cognitive challenges of Lyme as affecting seven cognitive categories.[i]

I’ve outlined these categories below. For each, I will explain what the impairment definition is, what it felt like for me in my worst days, and what improvements I’ve seen with remission.

- Attention and mental tracking

What it means: An inability to focus on one task through to completion or to multi-task

What I experienced then: If I was talking with someone and there was noise in the background, I couldn’t follow what was being said. Moreover, if I was writing even something as simple as an email, I could not endure any background noise, whereas, when I was in college I’d written papers with music playing and people talking all around me. I could complete tasks, but everything took longer than before. I sometimes had difficulty concentrating on a single task; it was hard for me to finish watching a TV show or reading an article without wanting to stop and do something else.

What I experience now: It’s still difficult for me to concentrate with background noise, though light instrumental music is okay. I can follow conversations with far greater acuity, and I can watch and process full-length TV shows and read articles and books. I can scroll through social media and process all the different things I’m reading without hindrance, and stay focused on the task at hand.

- Memory

What it means: Difficulty processing and retrieving information; forgetfulness

What I experienced then: I often could not remember the answers to questions as basic as “What’s your zip code?” or “Who’s the President?” It would take me several minutes to come up with the answer.

What I experience now: Sometimes it still takes me a moment to remember what I had for breakfast, but only when I’m overtired. The same is true for repeating conversations (telling a friend the same thing twice); I also have to remember that I’m getting older, too!). On the whole, I can process and retrieve information fast enough to navigate a busy city, give a lecture or facilitate conversation in my classroom. My long-term memory thankfully remains razor-sharp.

- Receptive language

What it means: Difficulty understanding written and spoken language; losing track of conversations, not being able to process ideas quickly enough to comprehend or respond in a timely fashion; difficulty reading

What I experienced then: There was a point when I could only process short emails and couldn’t even read a full magazine article. The words would blur in front of my eyes and I would read sentences over and over, trying to understand them. I’d lose track of what I was saying mid-conversation or even mid-sentence.

What I experience now: I can read full magazines and books, but pace myself in order not to get overwhelmed. I read and respond to many student essays. I read and easily process news articles. Once in a while, I’ll lose track of what I was saying, but that’s only when I’m tired or overwhelmed, and then I quickly self-correct.

- Expressive language

What it means: Difficulty communicating through written and spoken words

What I experienced then: When my grandfather was struggling with dementia, I’d watch him know what he wanted to say, but be unable to find the words. So he’d get frustrated and give up, and stop participating in conversation altogether. Sometimes, when I was very sick with tick-borne illnesses, that would happen to me. At other times my words would come out in a jumble. My doctor would ask for an overview of how I’d been feeling recently and I couldn’t summarize anything for him (I started keeping a written log of daily symptoms, so that I could put together a report for appointments).

What I experience now: I still keep that written log, but my ability to express myself has improved tremendously. I write weekly columns, have written two books, give lectures, and lead conversations all without issue. Occasionally I can’t come up with a specific word, but can usually get it when prompted.

- Visuospatial processing

What it means: Poor spatial relationships; vision difficulties

What I experienced then: My spatial relations have never been great, because I do not have binocular vision (I only see out of one eye at a time, which means I don’t possess depth perception). With Lyme, my capacity to experience spatial relations worsened. Sometimes I’d miss my mouth with the fork, or knock a glass before getting it into the dishwasher, or bump into furniture. Other Lyme patients find themselves getting lost or forgetting where they were going entirely.

What I experience now: My spatial relationships are still not very good, but I attribute these difficulties mostly to my previous vision issues.

- Abstract reasoning

What it means: The inability to grasp issues and reach conclusions, or the inability to understand the consequences of one’s actions.

What I experienced then: Sometimes conversations, which previously I would have been able to follow with ease, just seemed too high-level for me. It was as if my brain would “turn off” when people were discussing intellectual issues. This was frightening because I thought I had lost my intelligence and didn’t have anything worthwhile to say. Many Lyme patients thus afflicted might say or do things they would not have otherwise, which can take a toll on relationships.

What I experience now: I can process and synthesize information from multiple sources, recall it and contribute to a conversation. I’m a reflective person—over-analytical— so I overthink potential consequences too much, but that’s not always a bad thing.

- Speed of mental and motor processing

What it means: Inability to keep up with a lively conversation

What I experienced then: Returning to the feeling of one’s brain clogged with molasses, I processed everything very slowly. As mentioned earlier, it took too long for me to comprehend information and respond to it.

What I experience now: On most days, my head feels clear and I can process and express thoughts cogently. I’m best in the mornings, so I’ve learned to do creative work then, rather than in the late afternoons or evenings, and I always take an early afternoon nap. When I’m overtired, the brain fog can return, but it lifts much quicker than it used to, and I experience more sunny days.

Of course, this list begs the question, how did I get better? While there is no single protocol for everyone, my neurological symptoms improved through a combination of antibiotic and antimalarial medication, nutritional and homeopathic supplements, adjunct therapies like integrative manual therapy and neurofeedback, and an anti-inflammatory diet. For more ideas on addressing Lyme brain, check out the aforementioned book, or talk with your Lyme Literate Medical Doctor (LLMD).

Note: for patients with difficulty reading, my “Living With Lyme Brain” post is now available as an audio blog.

________________________

[i] Ducharme, Nicola McFadzean. Lyme Brain. California: BioMed Publishing Group, LLC, 2016 (9-12).

Related Posts:

Feed Your Body to Fight Lyme

Living with Lyme Brain

Dealing With Brain Fog

Jennifer Crystal

Writer

Opinions expressed by contributors are their own. Jennifer Crystal is a writer and educator in Boston. Her work has appeared in local and national publications including Harvard Health Publishing and The Boston Globe. As a GLA columnist for over a decade, her work on GLA.org has received mention in publications such as The New Yorker, weatherchannel.com, CQ Researcher, and ProHealth.com. Jennifer is a patient advocate who has dealt with chronic illness, including Lyme and other tick-borne infections. Her memoir, One Tick Stopped the Clock, was published by Legacy Book Press in 2024. Ten percent of proceeds from the book will go to Global Lyme Alliance. Contact her via email below.