.jpg)

Has your doctor recommended you get a PICC line to treat your Lyme disease? Here are the pros and cons of IV antibiotics for Lyme.

When diagnosed right away, many cases of Lyme disease can be treated with a three-week course of oral antibiotics. Some 20% of patients, however, go on to experience continued symptoms—known as Post Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome—and require more antibiotics. Still others, like myself, suffer with Late Disseminated Lyme Disease, which isn’t diagnosed until months or years after a tick bite. By that point, the Lyme bacteria, called a spirochete, has replicated and invaded many systems of the body, often crossing the blood-brain barrier.

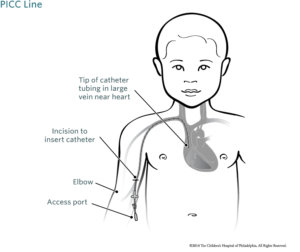

This stage of Lyme disease is so advanced that Lyme Literate Medical Doctors (LLMDs) often recommend intravenous antibiotics, administered through a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC line). A port is placed in your arm with a line that runs directly to your heart. The port remains in your arm for as long as your doctor recommends—in some cases months or even years—and you self-administer antibiotics. Just the idea of having a PICC line is understandably daunting to patients. Many write to me wondering if they should pursue this route. I responded briefly to this question in one of my “Dear Lyme Warrior…Help!” columns. In this blog, I will share more about my own experience with a PICC line, and outline pros and cons.

This stage of Lyme disease is so advanced that Lyme Literate Medical Doctors (LLMDs) often recommend intravenous antibiotics, administered through a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC line). A port is placed in your arm with a line that runs directly to your heart. The port remains in your arm for as long as your doctor recommends—in some cases months or even years—and you self-administer antibiotics. Just the idea of having a PICC line is understandably daunting to patients. Many write to me wondering if they should pursue this route. I responded briefly to this question in one of my “Dear Lyme Warrior…Help!” columns. In this blog, I will share more about my own experience with a PICC line, and outline pros and cons.

My Experience

I was bitten by a tick in 1997, but wasn’t diagnosed with Lyme disease and two of its co-infections, babesia and ehrlichia, until 2005. By that time the infections had crossed into my central nervous system, making them more difficult to treat. My LLMD had me start with oral antibiotics. At first, they caused a Herxheimer reaction, which told my doctor that the medication was working. However, after six weeks of treatment, he determined that it wasn’t working fast enough, and recommended a PICC line.

A nurse put the line in at the doctor’s office. It felt like getting a regular IV inserted; I could not feel the line moving from my arm to my heart. I had a chest x-ray to make sure the line was correctly in place, and then the nurse administered the first dose of antibiotics, to make sure I didn’t have a bad reaction. He also taught me how to administer the medication myself. Instead of a typical IV bag, the medication came in a bolus, a hard ball that needed to be refrigerated. The nurse showed me exactly how to wash my hands before touching my port; how to pinch the port with two fingers and clean it with an alcohol wipe; how to first flush the line with saline, and then how to attach the bolus; how to flush the line with saline and heparin (to prevent clots) once I’d finished infusing; and how to properly replace the port’s cap and safely wind it up, tucking it inside a mesh sleeve when I was done.

After a few days, I felt like a nurse myself. Armed with the right knowledge and my nurse’s phone number, I felt safe hooking my port up to a bolus twice a day. With my arm outstretched on the kitchen table, I read the paper in the morning and watched game shows at night to pass the hour that it took for the boluses to deflate. Once a week, the nurse came to my house to clean the line and draw my blood, so my doctor could run lab work to make sure I was reacting well to the medication.

When I wasn’t infusing medication, I generally was able to go about my day as normal (which, at that time of acute illness, didn’t include much beyond resting and taking the occasional trip to the pharmacy). I sometimes forgot the PICC line was even there. That said, I did have to take certain precautions with it. It was very important not to get even a drop of water on the line. Therefore, I wore a special sleeve to cover it when doing dishes or washing my hands; took baths instead of showers; and had someone else wash my hair in the sink. When out in public, I wrapped an ace bandage around the mesh sleeve that held my port in place, for extra protection; I had to be sure not to snag the line on anything. For that reason, I generally didn’t sleep on that side.

Despite these limitations and an unexpected gallbladder attack (which I’ll explain below), I am still glad I used a PICC line for the year that I had it in my arm. Would I have gotten better if I had stayed on oral antibiotics? Probably. Some LLMDs use them exclusively, even pulsing them on and off. But likely my recovery would have taken much longer. I saw great improvement in a year’s time, so the intravenous route was the right one for me.

When weighing whether it’s right for you, consider the following pros and cons:

Pros

- Efficacy and efficiency: Intravenous antibiotics are stronger than oral antibiotics, so they can attack spirochetes faster and more effectively.

- Pressure off the gut: Oral antibiotics can cause gastrointestinal issues such as candida. Intravenous antibiotics are a more direct route that doesn’t affect your stomach.

- Different medication options: Some antibiotics can be offered both orally and intravenously, while others work better in one form or the other. Intravenous antibiotics give your LLMD more options with which to treat your infection(s), and sometimes changing up treatment is helpful when you’ve hit a plateau.

- Medical know-how: Once you’ve had a PICC line and have self-administered intravenous antibiotics, other medical procedures seem like a snap. I learned so much from being my own nurse that I now feel better informed when asking doctors questions and advocating for myself, whether with Lyme or another illness.

- Weekly company: Lyme disease can be very isolating, especially when you’re too sick to leave the house. I looked forward to my nurse’s weekly visits for much-needed socialization.

Cons

- More intense Herxheimer reactions: Because a PICC line allows you to get a higher dose of antibiotics into your system faster, the die-off of spirochetes can also be quicker. Your body may not be able to eliminate the dead bacteria as fast as the antibiotics kill them. This can cause some intense Herxheimer reactions. Your doctor may give you a few days off of treatment to allow your body time to detox.

- Risk of gallstones: Gallstones are a rare side effect of certain intravenous antibiotics. I happened to get them, and had to undergo emergency gallbladder removal. That was in 2005. These days, LLMDs are more aware of which medications come with this risk (and tend to avoid them when possible), and are also able to prescribe proactive treatment against gallstones.

- Risk of clots: Following the proper protocol is essential to keeping a PICC line clean, but even so, the line can clot. This happened to me one night (I noticed when I couldn’t push the heparin into the line) and requires a nurse to come immediately. In some cases you may have to get the line removed, though my line was able to be repaired at home.

- Can’t get it wet: Having a PICC line means no swimming, and limitations on other activities like showering. There are special sleeves that you can wear when you’re near water (like when doing the dishes), but the arm absolutely cannot be submerged.

Only you and your LLMD can determine whether a PICC line is right for you. I hope this list will help you make an informed decision.

Related Posts:

Dear Lyme Warrior…Help!

What Does it Mean to Herx?

You Know Your Body Best

Turning Sickness into Strength: GLA Partners with Mighty Well

The above material is provided for information purposes only. The material (a) is not nor should be considered, or used as a substitute for, medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment, nor (b) does it necessarily represent endorsement by or an official position of Global Lyme Alliance, Inc. or any of its directors, officers, advisors or volunteers. Advice on the testing, treatment or care of an individual patient should be obtained through consultation with a physician who has examined that patient or is familiar with that patient’s medical history.

Jennifer Crystal

Writer

Opinions expressed by contributors are their own. Jennifer Crystal is a writer and educator in Boston. Her work has appeared in local and national publications including Harvard Health Publishing and The Boston Globe. As a GLA columnist for over a decade, her work on GLA.org has received mention in publications such as The New Yorker, weatherchannel.com, CQ Researcher, and ProHealth.com. Jennifer is a patient advocate who has dealt with chronic illness, including Lyme and other tick-borne infections. Her memoir, One Tick Stopped the Clock, was published by Legacy Book Press in 2024. Ten percent of proceeds from the book will go to Global Lyme Alliance. Contact her via email below.