By Hannah Staab & Mayla Hsu, Ph.D.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently announced that diseases spread by mosquitoes, ticks and fleas tripled between 2004 and 2016. More than 640,000 of such illnesses were reported during these years, including Zika, dengue, chikungunya, Lyme disease and plague. These diseases are known as vector-borne diseases, because infection of humans requires transmission of the microbe by an intermediate species. The CDC acknowledges that the US is inadequately prepared to diagnose and treat these expanding epidemics, which are fueled in part by climate change and its effects.

For example, migratory birds have been linked to the spread of West Nile virus, avian influenza virus, Lyme disease, and many other illnesses. Etc. etc.

Migratory birds have been linked to the spread of West Nile virus, avian influenza virus, Lyme disease, and many other illnesses. Climate change is altering the amount of suitable habitats for disease-carrying animals such as ticks. Even though many new habitats now provide ideal living temperatures for ticks, it would be difficult for them to physically move to these new areas without some help. Migratory birds facilitate the movement of ticks to new territories. Avian migration has opened the door for many diseases to spread over vast distances each year by carrying disease vectors such as ticks, or by the birds being themselves infected by the disease and spreading it to others as they migrate.

To see the effect of bird migration on the spread of ticks across America, Cohen et al. (2015) conducted a study that measured how many ticks are brought into America by migratory birds. They also screened the ticks for various microbes, including pathogens that cause spotted fever, and the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. In the spring of 2013 and 2014 they captured 3,844 birds, of 85 different bird species that were returning north for the summer. Out of these 137, about 3.56%, were infected with ticks. All of the ticks collected were either in the larva or nymph stage of development, and 67% of the ticks they collected were neotropical ticks, meaning they were from Central or South America. After screening the ticks for diseases, they found that 38 of the ticks were infected with some variation of the spotted fever bacteria, Rickettsiae, and that none of the ticks harbored Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme.

The authors estimated that about 4 to 39 million neotropical ticks are brought to the United States each year. Although the ticks found in this study did not have Lyme, migratory birds are still introducing ticks to new habitats thus increasing tick populations across the country. Since the ticks they found were all larvae or nymphs, there was still a chance for them to become infected with Lyme, and spread it to future hosts. Ticks have three blood meals in their lifetime, one to help their development from larvae to nymphs, another for their transition from nymphs to adults, and finally, as adults before laying eggs. The Lyme bacterium or other pathogens are transmitted to ticks if one of their blood meal hosts is infected. Thus, the ticks that are transported to America on birds can still put humans at danger for Lyme disease, if they acquire their next blood meal from an infected host.

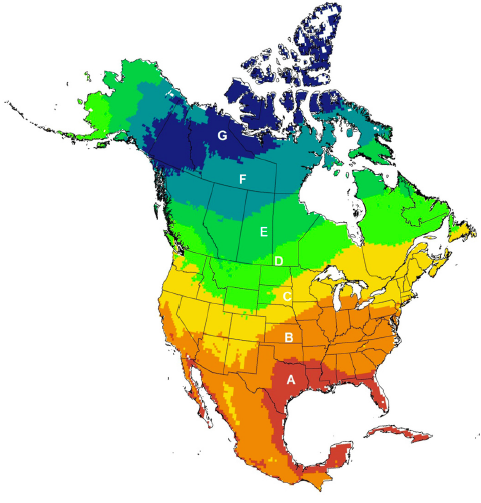

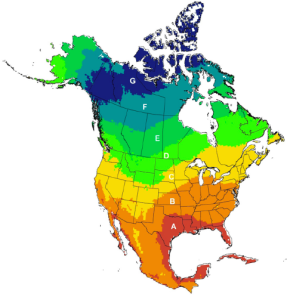

Ogden et al. (2015) conducted a somewhat different study examining the relationship between migratory birds and ticks. The study tracked how far north the birds were taking the ticks. They found that many birds went further north than their previous breeding sites when returning to Canada in the spring, and even went into territories beyond the tick’s climatic range (Figure 1). Even though ticks cannot currently survive in some of these areas, the increasing temperatures will make more and more of these habitats suitable over time. Climate change will also impact the migration routes of birds, and perhaps cause them to continue flying further north each year. Therefore birds will continue to bring ticks into new habitats, and the ticks will be more likely to survive in these northern areas as the temperatures continue to rise. Moreover, with rising temperatures, mice will also expand further north, possibly bringing the Lyme disease bacterium with them.

Ticks are very small, slow moving creatures; alone, it would be impossible for them to spread into new territories as far as northern Canada. However, ticks receive a lot of help from the small animals they latch onto, with organisms like migratory birds helping them cover vast distances. The actions of migratory birds amplify the effects of climate change on tick populations, and together they will help spread ticks into new territories. There can be little doubt that Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases will follow.

Figure 1. Regions used to assign birds to latitudinal bands in the Ogden et al. (2015) study. The results indicated that up to 70% of birds carrying ticks could bring them north of their capture locations (into bands C, D, and E), and up to 17% could transport ticks further into the boreal region of eastern Canada (bands D and E). This map shows how far north these ticks are being transported. Adapted from Cohen et al., 2016, Journal of Environmental Microbiology Vol. 3 page 322-350.

For more on Lyme disease and climate change, click here.

*This blog post has been updated in June 2018 to include the CDC announcement of May 2018.

GLA

Admin at GLA