by Jennifer Crystal

Lyme disease isn’t the only illness you can get from a tick bite

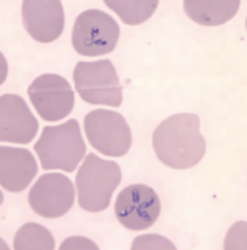

Babesiosis, a tick-borne infection caused by the parasite Babesia (most commonly, Babesia microti, though there are other species like Babesia duncani and Babesia divergens), is a malaria-like infection of the red blood cells. A 2019 report by the American Academy of Pediatrics states, “Although cases of tickborne babesiosis have been diagnosed in the U.S. since 1966, this disease only became nationally notifiable in 2011. A report of the first five years of babesiosis surveillance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows an alarming increase in incidence.”[i]In his book Why Can’t I Get Better? Solving the Mystery of Lyme & Chronic Disease, Richard I. Horowitz, M.D. speaks to this alarming prevalence: “Other studies are now showing evidence of a worldwide epidemic of babesiosis: It is now spreading to parts of the United States, Europe, and Asia…the scientific literature has shown that the number of positively diagnosed cases of babesiosis in New York state alone has increased twenty times.”[ii]

While increased Lyme literacy has improved awareness of babesiosis, many people still look at me like I have three heads when I say I have this infection. The name is indeed strange and difficult to pronounce; one of my graduate school professors said, “Can we just call it babelicious? That’s easier.” Whether you refer to it as babesiosis, Babesia, babelicious, or, as my friends have adopted, babs, it’s important that you understand what this illness is, how it is transmitted, what the symptoms are (and what they actually feel like), and what treatment options are available.

The tiny parasite Babesia is most commonly transmitted by a tick bite—meaning you can get Lyme and babesiosis, as well as other co-infections, all from the same tick. However, you do not have to have Lyme disease to get Babesiosis. Babesia can also be transmitted via blood transfusion or from mother to fetus. It depletes the red blood cells of oxygen, causing patients to experience air hunger, lightheadedness, weakness, shortness of breath, and post-exertional fatigue akin to what marathon runners describe as “hitting a wall”. Other common symptoms include high fever, night-sweats, headaches, chills, and hypoglycemia. Dr. Horowitz writes that babesiosis can also cause “a hemolytic anemia (due to red blood cells breaking down), jaundice, thrombocytopenia (low platelet count), congestive heart failure, and renal failure.”ii

What does it actually feel like to have babesiosis? While every case is different and not all patients experience every symptom, I can share my own 20+ year battle with this infection. After finding a splotchy red rash on my arm in the summer of 1997, the first symptom I experienced was hypoglycemia. After a busy morning teaching water-skiing, swimming, and canoeing at the summer camp where I worked, I collapsed in the dining hall from what I thought was dehydration but was actually low blood sugar. Beyond testing for diabetes, no one thought to look into the cause of my sudden hypoglycemia or to test for tick-borne infections. Instead, I continued to suffer low blood sugar reactions and sudden lightheadedness for years, and learned to always carry a snack with me.

As the tick-borne infections Lyme, babesiosis, and ehrlichiosis ran through my body unchecked over the next eight years, I developed smashing migraines that left me nauseous and crying on the bathroom floor. I now know that my brain was not getting properly oxygenated, causing my extreme pain. I lived in Colorado at the time, so doctors told me I had altitude sickness.

Babesiosis can exacerbate Lyme and other infections; not knowing I had any of them, they all were getting worse, the symptoms overlapping and manifesting more frequently. Flu-like symptoms, coupled with intense bouts of fatigue, came on-and-off for years. Despite being a gym rat and a life-long skier, I could no longer keep up with my friends on the slopes, experiencing low blood sugar, dehydration, and fatigue that would sometimes send me to bed for a day or two afterwards. By the end of my second year in Colorado, I’d developed asthma and needed to use an inhaler.

In 2003, I got mononucleosis that slipped into chronic Epstein-Barr virus—I couldn’t fight it because of the underlying tick-borne diseases—and in 2005 those diseases were finally diagnosed. By that point I was experiencing fevers that could have been associated with any of those illnesses, and occasional nightsweats.

Once I started treatment for babesiosis (along with antibiotics for Lyme and ehrlichiosis), those nightsweats increased, but that was a good sign. It was a form of Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction; my body was sweating out the dead parasites. I often woke in a puddle, my pajamas fully soaked, and sometimes had to change sheets twice a night. At my worst point, I couldn’t ride thirty seconds on a stationary bike without “hitting a wall”.

While Lyme Literate Medical Doctors (LLMDs) have varying opinions about the treatment and prognosis of babesiosis infections, the general consensus I heard at the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society (ILADS) conference in 2019 was that there is no cure. Some doctors are having great luck, with patients reporting complete eradication of symptoms for both babesiosis and Lyme disease, with the antimicrobial drug Disulfiram (commonly known as Antabuse); however, more research is needed, and the drug has serious side effects. More commonly, doctors use anti-malarial drugs such as Mepron, Malarone, or Coartem to treat babesiosis, often pulsing these treatments over weeks or even months as the patient’s Babesia load decreases. Still others supplement these medications with homeopathic remedies such as artemisinin or cryptolepsis.

This is not a complete list of babesiosis treatments; Dr. Horowitz talks about others in his book, and your LLMD may have other ideas. I have been on different anti-malarial medications, paced at different intervals, and on different homeopathic drops, throughout my journey. Unfortunately, it doesn’t help for me to share my protocol, because it is ever-changing, and because no two cases of tick-borne illness are alike. Here’s what I can tell you for sure: babesiosis symptoms can get better. If you are being treated for Lyme disease and haven’t been tested for babesiosis or other co-infections, you may only be fighting half the battle. Whether you have a known or suspected case of Lyme, it’s critical that you talk to your doctor about other tick-borne diseases, too.

[i] http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6806a1.

[ii] Why Can’t I Get Better? Solving the Mystery of Lyme & Chronic Disease. Horowitz, Richard I., MD. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2013 (135, 136).

Related Posts:

Differentiating Between Babesia and COVID-19 Air Hunger

New test for Babesia approved by the FDA

What is Air Hunger, Anyway?

Tainted Transfusions: Why Screening Blood is More Important Than Ever

Opinions expressed by contributors are their own.

Jennifer Crystal is a writer and educator in Boston. Her memoir about her medical journey is forthcoming. Contact her at lymewarriorjennifercrystal@gmail.com.

Jennifer Crystal

Writer

Opinions expressed by contributors are their own. Jennifer Crystal is a writer and educator in Boston. Her work has appeared in local and national publications including Harvard Health Publishing and The Boston Globe. As a GLA columnist for over six years, her work on GLA.org has received mention in publications such as The New Yorker, weatherchannel.com, CQ Researcher, and ProHealth.com. Jennifer is a patient advocate who has dealt with chronic illness, including Lyme and other tick-borne infections. Her memoir, One Tick Stopped the Clock, was published by Legacy Book Press in 2024. Ten percent of proceeds from the book will go to Global Lyme Alliance. Contact her via email below.

-2.jpg)