By Hannah Staab

Climate change has the potential to expand the incidence of Lyme disease. For example, shifting environmental conditions in ecosystems in the northeastern United States may contribute to the rising prevalence of Lyme disease in Canada. Lyme disease is spread by bites of black-legged ticks, and is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, bacteria that live in the tick midgut. As the geographic range of ticks and the bacteria expands northward due to regional warming, new human and animal hosts are now at risk of infection.

Ticks thrive in a specific temperature range, and if the environment is too cold, their metabolism cannot function at a high enough level to reproduce or look for a host to provide their next blood meal. Therefore, increasing global temperatures allow ticks to proliferate in areas that would normally be too cold to support their growth.

Not only are warmer temperatures providing ticks with new habitats, they also help the ticks in one of their most important pursuits, finding a host. In order to mature and reproduce, ticks require three separate blood meals from vertebrate hosts in their lifetime. To find the source of their meal, ticks engage in “questing behavior”, in which they climb to the top of blades of grass or vegetation to get a better chance of clinging onto a passing host. However, the tick’s ability to make this great climb is dependent on two factors, temperature and humidity. Studies have shown that ticks are more likely to quest in higher temperatures, due to the boost that temperature has on metabolism.

One study by Tomkins et al. (2014) sampled ticks from three areas in the UK, including northeastern Scotland, northern Wales, and southern England. They also studied ticks from France, one site at low, and another at high altitude. The climates in each of those locations vary from cool to warm, with annual mean maximum temperatures ranging from 9.9°C to 16°C (49.8°F to 60.8°F). Ticks from cooler habitats started questing at lower temperatures, and had a lower maximum tolerated temperature, showing their adaptation to their specific environments. The study also examined how the ticks from different regions responded to increases in temperature, and discovered that ticks from colder climates were more sensitive to changes in temperature than ticks from warmer areas. It’s possible then, that ticks in northern regions will start questing at even slight temperature increases. Therefore, a warmer climate would mean that ticks could have the opportunity to quest more frequently, and increase their chances of latching onto a host.

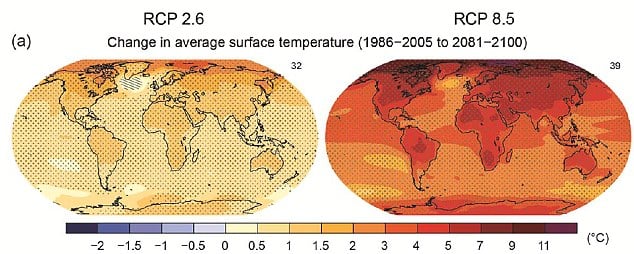

Global warming will lead to shorter and more favorable winters for ticks, increasing both the time that they are able to quest, and the frequency that they will find a host. A study by Simon et al. (2014) revealed that warmer temperatures are associated with northern expansion of the Peromyscus leucopus, the mouse species that serves as blood meals for tick nymphs, providing them with the resources to molt into adults, which then potentially infect larger mammals, including humans. Lyme disease has been emerging in Canada, and this study suggests that it is most prevalent in those areas where both mice and ticks have successfully expanded their range. This study predicts that by the year 2050, the black-legged tick will have expanded about 186 miles, the white-footed mouse will expand about 155 miles, and the range of the Borrelia burgdorferi bacterium will move about 93 miles further north in Canada. During the last 15 years, Lyme disease has been spreading at a rapid rate in the US. With projected changes in temperature, there will be even more factors favoring Lyme proliferation, making it even more important for us to act now.

To tackle the coming wave of Lyme disease prompted by climate change, we can mitigate our impact on the environment by being conscious of our energy consumption, reducing our carbon footprints, generating less waste, eating locally, and conscientiously managing land use to reduce human exposure to areas with a high tick presence. However, temperatures are already on the rise, and Lyme disease is already expanding into new regions. Therefore, in addition to fighting climate change, we must redouble our efforts on Lyme disease research, so that we can be better prepared to care for the rising number of patients suffering from this debilitating disease.

For more on Lyme disease and climate change, click here.

GLA

Admin at GLA