by Jennifer Crystal

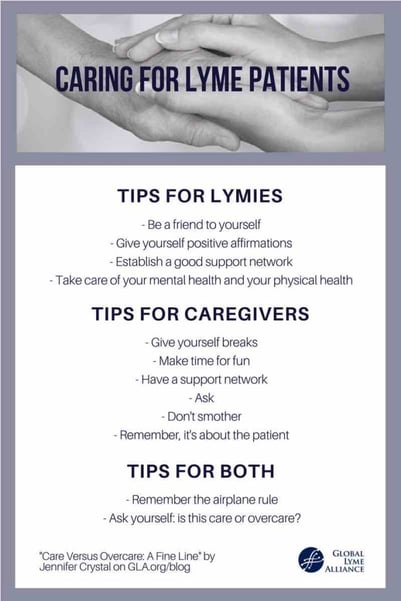

Well-meaning Lyme caregivers can easily cross the line from care to overcare. Here are some simple rules to follow for both patient and caregiver.

Recently a friend was going through a difficult time. When she confided in me, I offered her a non-judgmental ear and lots of hugs. I gave advice when she asked for it. Being there for her made me feel good. Indeed, as Doc Childre and Howard Martin describe in The Heartmath Solution, “care inspires and gently reassures us. Lending us a feeling of security and support, it reinforces our connection with others. Not only is it one of the best things we can do for our health, but it feels good—whether we’re giving or receiving it.” [1]

But then, as my friend’s problem became more serious, I became deeply worried about her. Her situation was on my mind often, and I started checking in with her in an overbearing way. I was anxious about her all the time. While my feelings came from a place of love and concern, I had crossed into the dangerous territory of overcare.

Childre and Martin define overcare as “a burdensome state…when care from the heart is bombarded by niggling worries, anxieties, guesses, and estimations from the head.” They caution it is “one of our biggest energy deficits, and it’s at the root of a lot of other unpleasant emotional states, including anxiety, fear, and depression.”

The line between care and overcare is so fine that it can be hard to distinguish the two. However, it’s important to be able to do so, to protect our own well-being and our relationships. This is especially true—and difficult—for Lymies and their caregivers.

While Lymies may take care by following doctor’s orders, we can have a hard time enacting self-care, because we are plagued by feelings of guilt and shame. Instead of being gentle and patient with ourselves, we spend time and energy wondering when or if we’ll get better, beating ourselves up for being sick, and worrying that we are burdens. I spent years doing this. I see now that I was in a detrimental state of overcare, which hindered my ability to get well.

Well-meaning Lyme caregivers can easily cross into overcare, too. Many work tirelessly to care for their children, parents, siblings, or friends who are sick. That much care is greatly appreciated, but can easily be taken too far, to the point where the caregiver gets burnt out. Once they hit that point, they’re not helping the Lymie or themselves. Moreover, when a caregiver over-identifies with a problem, getting too involved and worrying to the point that their own mental health is affected, the patient may feel smothered or guilty. Everyone loses.

So how do patients and caregivers negotiate this fine line? Here are some lessons I’ve learned along the way.

For Lymies:

- Be a friend to yourself. Be as kind to yourself as you would to a friend going through the same thing. Would you make that person feel guilty or ashamed for being sick? Give yourself the love, care, and understanding you would give to someone else.

- Give yourself positive affirmations. Instead of berating yourself, try out thoughts like, I’m doing a good job. I’m going to get through this. This is not my fault. Sometimes this disease is two steps forward, one step back, but ultimately I am moving in the right direction.

- Establish a good support network. This could include a therapist, friends, family members, other patients—anyone who understands your situation, gives you the empathy you need, and can talk through your worries and concerns.

- Take care of your mental health and your physical health. Any long term illness causes situational anxiety and depression, and neurological Lyme can make them worse. Personally, seeing a therapist and treating my anxiety and depression have helped me to physically heal from Lyme.

For Caregivers:

- Give yourself breaks. Even if you are the primary caregiver of a patient, make sure you have other people who can fill in for you so that you can take time off.

- Make time for fun. Don’t just take a break to shower or go to the pharmacy. Take yourself out for an ice cream cone, see a movie, or do an activity you enjoy. You are not neglecting the patient by doing this; you are recharging your own batteries so that you can continue to care for your loved one.

- Have a support network. Have a therapist, friend, or family member you can talk to about the emotional toll of being a caregiver. Try to direct your worries to this person rather than to the patient.

- Ask. Never assume that you know what a patient needs. Ask specifically how you can best help them.

- Don’t smother. No one likes to be fussed over for too long. Depending on your relationship with the Lymie, establish a routine that’s comfortable for both of you: maybe you talk by phone briefly when the patient is feeling up to it; maybe you send one check-in text a day; maybe you stop by once a week for a quick visit.

Remember, it’s about the patient. As a natural giver, this is one I struggle with the most. My instinct is to help, but I have to first be sure someone wants my help. I have to see if the concern I’m giving is about my need to show I care, or if it’s about the person getting the care they need.

Remember, it’s about the patient. As a natural giver, this is one I struggle with the most. My instinct is to help, but I have to first be sure someone wants my help. I have to see if the concern I’m giving is about my need to show I care, or if it’s about the person getting the care they need.

For Both:

- Remember the airplane rule. On a plane, you have to put your own oxygen mask on first before helping others with theirs. First and foremost, you must always take care of yourself.

- Ask yourself: is this care or overcare? Keeping yourself in check based on the definitions above will help you to give healthy rather than detrimental care. Checking myself when I went into overcare with my friend helped me to be a better friend to her and to take better care of myself.

[1] Childre, Doc and Martin, Howard. The Heartmath Solution. HarperSanFrancisco, 1999 (159, 165).

Opinions expressed by contributors are their own.

Opinions expressed by contributors are their own.

Jennifer Crystal is a writer and educator in Boston. She is working on a memoir about her journey with chronic tick-borne illness. Contact her at jennifercrystalwriter@gmail.com

GLA

Admin at GLA